Blog: Communities, Conservation, and Livelihoods: A Win-Win Situation

CEESP News -- Indu Kumari, Wildlife Trust of India

The communities living on the fringes of protected forests are considered exploiters by some, while others feel that they are victims. The latter view holds that they had been living in harmony with nature for centuries but are now being deprived of natural resources, resulting in extreme poverty at times.

It was a pleasant surprise for me to see that the delegates of the Communities, Conservation and Livelihoods Conference, Halifax, Canada, May 28th-30th 2018 (by IUCN-CEESP & CCRN) had an understanding about the need to work on human development, welfare and well-being of communities for conservation.

The delegates were having similar issues across the world where they were being questioned on why we need to work on issues of human-wellbeing when we talk about ecosystem conservation. The human welfare agencies felt that these communities were a subject of wildlife and forest department while the wildlife sector felt that the direct species and ecosystem conservation activities and its management were more important. One of

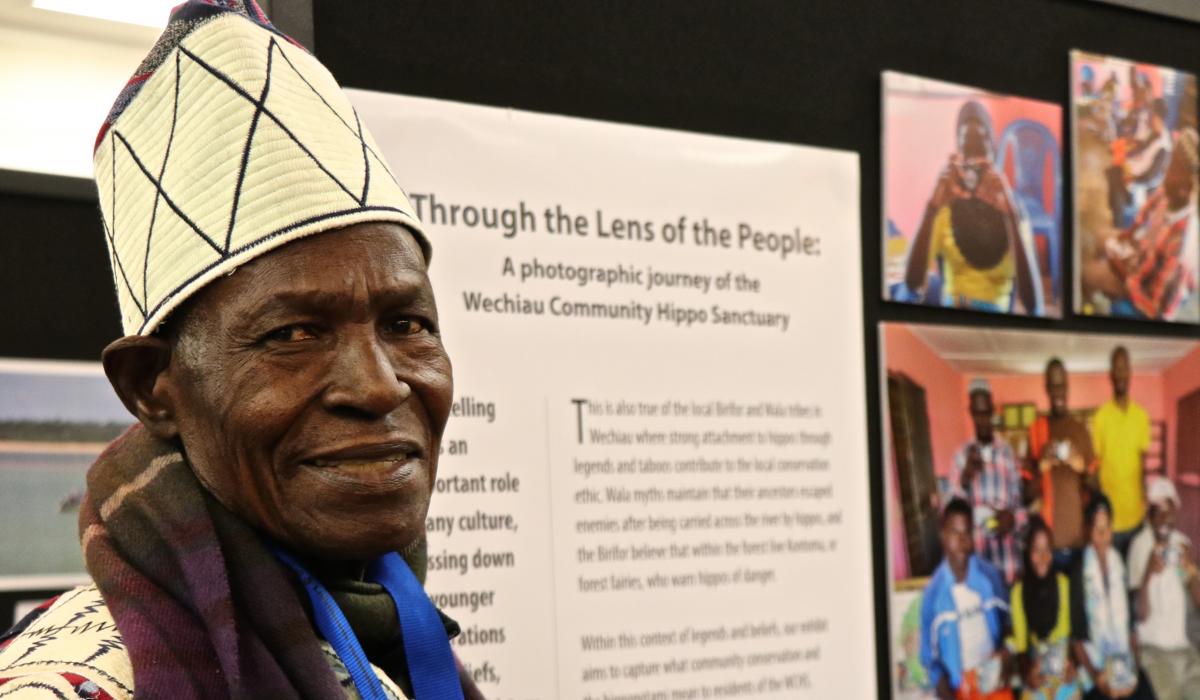

Photo: Iben Munck

Photo: Iben Munck

To understand the situation, we must place it in a historical context. Communities living next to forests once felt a sense of ownership towards them and therefore managed them with sustainable systems of extraction and use for self-sustenance. This association was strengthened by the engraining of forests and wildlife into art, culture, religion and tradition. With time, however, as human populations grew the daily needs of forest communities began to increase. Further, people began to understand the economics related to wildlife and forests and the larger demands that industry had for raw materials sourced from wild lands.

Indu Kumai presenting on community partnerships through handicraft livelihoods. Photo © Iben Munck

The old systems of knowledge began fading and cultural traditions either became symbolic or downright exploitative, for instance in the form of mega hunting events. Then the big brunt was the ever-escalating demand for land for increasing population and industrialization. The government took heed of these developments and started protecting and managing wildlife and forests by designating forest areas as national parks and wildlife sanctuaries. This also resulted relocation of forest communities and in the detachment of forest fringe village communities from nature. Since they were not a part of the new system they gradually lost the sense of ownership they had felt towards forests. Some community members, whether due to need or greed, began to see forests as an unutilised resource at their doorstep and started finding ways to access them legally or illegally.

The present understanding, at least among people in the forest villages I have worked in, is that forests belong to the government, so the government is protecting them. Others still associate forests with livelihood, medicine, food, fuel and fodder, but feel that the wild animals are of the forest department and that they are a nuisance, simply creating conflict. In some communities when I ask the question ‘what are the benefits from forests?’ the first response is ‘none’!

The wisdom that links wildlife to forests to better climate to water to food, fuel and fodder is unfortunately now mainly confined to books and the internet, whereas it needs to be established once again among forest communities.

But how? Do people from cities have the moral authority to go to these deprived communities and lecture them about the value of forests? To tell them that they should not selfishly exploit the forests that have sustained them for ages? That they should appreciate the precious wildlife around them and not allow it to go extinct?

Even if a more indirect approach were suggested to engage with communities, such as through street plays or posters explaining the value of forests, I would argue that in most areas there is a complex web of issues that must be dealt with before they are empowered enough to be the protectors of their natural heritage once again.

Photo: Indu Kumari

Photo: Indu Kumari

Participants posing with a needle-felt sculpture by One Square Meter. Through the creation of these pieces, women from pastoral communities are able to exchange knowledge, as well as raise funds for their community.

Poverty: Extreme poverty makes the fringe communities heavily dependent on the forest for food, fuel, fodder and building materials. Poverty is further related to lack of skills, education and resources (like land and raw materials), and therefore the lack of reliable livelihoods. This is a vicious circle leading to migration, exploitation, malnutrition, ill-health and unsustainable extraction of natural resources. It can be addressed by providing alternate livelihoods, alternate fuels, and alternate sources of fodder, food and water through sustainable agriculture methods, agroforestry, plantations and watershed management.

When I met the communities living besides the Nagzira-Navegaon Tiger Reserve, India, in 2010 I saw the dependence clearly visible and how the thin forest patch was in a verge of collapsing if something was not done. The community which mainly consisted of marginal farmers and daily wage labourers didn’t realize how heavily they were dependent on the forest and the relevance of that thin patch in reducing their direct conflict with wild animals. The question of the importance of the forest in providing ecosystem services was beyond imagination. The project started by reducing the high dependence on forests for fuelwood and livelihood. This has now reached to a stage where the dependency has been reduced by 40% in the Wildlife Trust of India (WTI) project villages and the villagers have started realizing the importance of forest around them.

Empowerment: India’s population has grown almost four-fold since independence. There is a dearth of land for agriculture, housing and industry, so people look towards the forests for land. The communities that have been given the power to rebuff advances from industry through social audits either don’t understand the link between wildlife and forests and their own wellbeing, or give their consent due to other reasons or pressures. The communities themselves encroach or clear the forests for agriculture and other needs arising out of economic necessity. This can be addressed by creating ownership and empowerment within the community. These communities have sustainably fulfilled their economic needs from the forests for many ages and have the skills for it. Since the situation is changing, it is important that their economic needs are catered to, by providing training and support for sustainable agricultural methods and alternative livelihoods.

Vulnerability: These communities must realise that they are highly vulnerable to the loss of the forests and wildlife, which would lead to natural disasters, desertification, landsides, water shortage and climate change. They are after all the ones who face the first brunt of nature’s wrath when their food and fodder sources are exhausted, when water bodies dry out or their houses and lands are lost to floods and landslides. Therefore, they must protect the forest to live. I met one such community in Jharkhand where Ajeevika livelihood programme was working on poverty reduction. The villagers in a small village in Deogar district lived very close to the hills with lush green forest and were exploiting it for fuel, non-timber forest products, fodder and farming. The project team found that drinking water was scarce and the village suffered due to mudslides. Our team educated the community that this situation was due to the depleting forest cover in the hills, leading to removal of top soil and moisture loss. The community decided that they would stop wood extraction from the forest as the livelihood support was being provided by the project. They agreed to use crop residue and twigs from farmed trees for fuel. Each house voluntarily protected the forest by turn from other extractors and within few years the forest came back and the water table rose.

Sustainable Production and Consumption: The community must understand that the need for the forest transcends economic use: it is a giver of life. For this the community should be self-reliant for food, fodder and fuel production. The solution could be support for watershed development, livelihood skill enhancement, and sustainable production of food, fuel and fodder.

With the heavy influx of tourists and changing consumption patterns the issue of waste management has also multiplied in these areas, to the extent that wild animals have been seen consuming plastics. The solution could be to empower communities to manage tourism in their area.

Thus, when a community’s vulnerabilities are addressed through empowerment, sustainable livelihoods, technical knowledge, education, proper health and infrastructure, it will no more be an exploiter of forests. People will take pride in their natural heritage and once again become its custodians, as they will understand that forests have sustained them for ages and the lives and livelihoods of future generations are dependent on them.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Indu Kumari is Manager & Head, Green Livelihoods, at Wildlife Trust of India (WTI). She has been working in the field of community development for over 12 years. At WTI she works with various forest and wildlife dependent communities on issues of livelihoods, clean energy, gender and health, across several Indian states. She is also a member of the IUCN-Commission on Environmental, Economic and Social Policy (CEESP) and, a member of the IUCN-World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA).