OECMs: a new conservation opportunity for Viet Nam

The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), to which Vietnam is party, has agreed a new conservation designation that complements protected areas. Vietnam has an opportunity to extend and connect its conserved areas by identifying and legally recognizing “other effective area-based conservation measures” or OECMs.

Protected areas in Vietnam

The earliest protected area law was the Minister of Forestry’s Decision 1171 on Special Use Forests in 1986. Seven nationally managed national parks, and 49 provincially managed nature reserves were established. In 1999, MARD decided to expand the area under protection from 1 million to 2 million hectares. This led to the establishment of total of 10 national parks, 53 nature reserves, 17 Species & Habitat Conservation Areas, and 21 Landscape Protected Areas covering almost 2.3 million hectares.

In 2014, Prime Minister’s Decision 1976 proposed expanding coverage to 2.4 million hectares, or about 7% of Vietnam’s land area, by 2020 and today coverage has almost reached this target. Nevertheless, there is little prospect of Vietnam legally protecting 17% of its land area by 2020 as defined by CBD Target 11:

By 2020, at least 17% of terrestrial and inland water, and 10% of coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services, are conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well connected systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, and integrated into the wider landscapes and seascapes.

One reason for the slow-down in expanding the protected area network over the last 20 years is competition over land and water in a rapidly developing country of 96 million. Another factor is the limited funding available for protected area management. With resources stretched thin and management effectiveness already low, there is little appetite to add to the protected area coverage.

OECMs in Vietnam

Target 11 refers to “other effective area-based conservation measures”. IUCN provided technical advice to the CBD to define OECMs and in 2018 the CBD adopted the following definition:

A geographically defined area other than a Protected Area, which is governed and managed in ways that achieve positive and sustained long-term outcomes for the in situ conservation of biodiversity, with associated ecosystem functions and services and where applicable, cultural, spiritual, socio-economic, and other locally relevant values.

OECMs are an opportunity to both recognize the contributions to the conservation of biodiversity occurring outside of protected areas and to incentivize conservation outside of protect areas through recognition and support. Vietnam is home to several large agricultural dominated landscapes that include areas of high biodiversity value and/or are the target of restoration to reestablish natural ecosystem functions for climate change and biodiversity benefits. Within these landscapes there are opportunities to recognize OECMs.

Examples include:

In the Mekong Delta, a key aim of Resolution 120 issued in 2017 is to de-intensify rice production to reconnect the Mekong’s flood plain and restore ecosystem functions. This opens up the possibility of transitioning hundreds of thousands of hectares in the upper delta out of the third or even second rice crop into higher value flood-friendly livelihoods. As well as increasing flood and drought resilience, this will restore capture fisheries and aquatic and agro-biodiversity. Parts of these restored areas may be recognized as OECMs.

In the Central Highlands, there is a need to transition out of coffee monocultures into mixed agroforestry by intercropping coffee and fruit trees such as durian, passion fruit, and avocado. This new crop mix is high value and uses much less water, thereby mitigating growing dry season water shortages. If this transition were combined with strict protection of the remaining areas of natural forest, significant areas have the potential to be recognized as OECMs since they deliver biodiversity, as well as social and economic benefits.

In Hanoi, there is an opportunity to convert the southern tip of Bai Giua Song Hong, the 300-hectare island in the middle of the Red River, into one of the city’s few green spaces. 300 species of bird have been recorded there. Until recently the island was regularly flooded, which limited development to banana farms. But with the river now regulated by the Hoa Binh dam, flood risk has diminished and the island has become prime real estate. Several big companies are interested in developing the island and it may be possible to integrate an OECM into these plans.

OECMs also offer opportunities to recognize the contributions that businesses can make toward biodiversity conservation. TH Milk, one of Vietnam’s largest dairy companies, has proprieties in Nghe An Province, including a 50-hectare sugar factory. Most of this land is made up of lakes and grasslands that have been untended and allowed to “re-wild”: chemicals aren’t used, the grass isn’t cut, dead trees aren’t removed, and the insect and bird life have exploded. Because it is so well protected, the property could be used to reintroduce turtles that have been wiped out in the wild. Such an area could meet the criteria of OECM.

Identifying OECMs

IUCN has prepared guidelines for recognizing and reporting OECMs and a draft methodology for identifying OECMs (https://www.iucn.org/commissions/world-commission-protected-areas/our-work/oecms/oecm-reports).

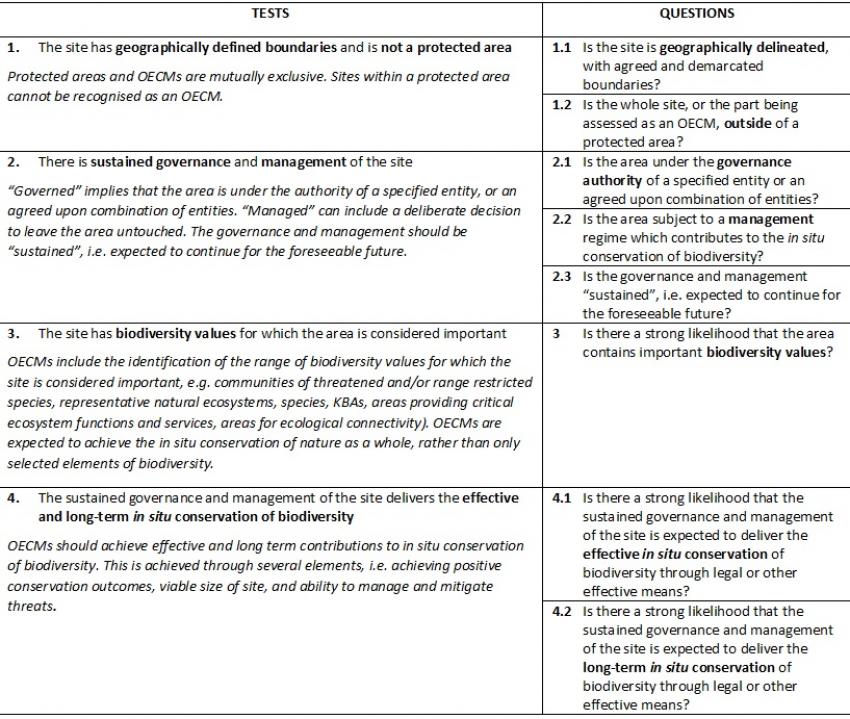

An OECM must meet four conditions. It must be outside a protected area; it must have geographically delineated boundaries, a sustained governance authority and management regime; it must be delivering effective in situ conservation of biodiversity; and it must have the potential to conserve biodiversity over the long-term. These conditions set a high standard for compliance in order to avoid poorly managed areas of limited biodiversity value being considered as OECMs

The following table summarizes these four conditions, or tests, and associated questions:

Photo: Four conditions of OECM © IUCN Viet Nam

Photo: Four conditions of OECM © IUCN Viet Nam

MONRE's potential role

MARD manages the national protected area system. But this covers only a small portion of the land area and there are many high conservation areas that are unprotected and unrecognized. As the government agency responsible for biodiversity conservation, MONRE has the mandate for mainstreaming biodiversity in land use outside protected areas.

One way for MONRE to do this is to recognize and report on OECMs once the necessary legislation is in place. The revised Environmental Protection Law, which will be submitted to the National Assembly in 2020, and the Biodiversity Law are opportunities to define OECMs in law. Once OECMs have been recognized in law, MONRE would need to draft the implementing regulations, which could be done by adapting the global guidelines that IUCN has prepared to the Vietnam context.

Once the OECM implementing guidelines are in place, MONRE would need to work with businesses, farmer groups and cooperatives, forest management boards, provincial governments, and other bodies that manage large areas of land with high biodiversity value to identify potential OECMs. This role would play to MONRE’s strengths as a standard setting and regulatory, rather than a land management agency.

By implementing OECMs, MONRE would significantly increase its role in in situ biodiversity conservation in ways that complement rather than compete with MARD. This approach would not only assist Vietnam meet its international conservation commitments but also allow it to protect some of the most biodiverse but threatened habitats, such as isolated karst hills, seasonally flooded grasslands, and coastal mudflats that are poorly represented in the protected area system.