Opportunities and challenges in expanding wind in Vietnam’s electricity mix

This is the fourth in a series of six web stories exploring how Viet Nam can implement its COP26 energy commitments while minimizing environmental impacts and making progress on broader sustainable development goals. Other pieces explore topics like international finance for renewable energy and how Viet Nam can protect the natural productivity of the Mekong Delta by investing in alternatives to the Sekong A dam in Lao PDR.

Photo: Wind power factory in Dong Hai 1, Tra Vinh Province © Trung Nam Group

As Viet Nam races to meet its ambitious COP26 net-zero commitment by 2050, wind power is emerging as a major contributor to the energy mix. Although Viet Nam has added 16,000 MW of solar since 2019, the Power Development Plan 8 (PDP8) anticipates that wind not solar power will drive the next phase of Vietnam’s renewable energy transition.

Current Status of Wind in Viet Nam

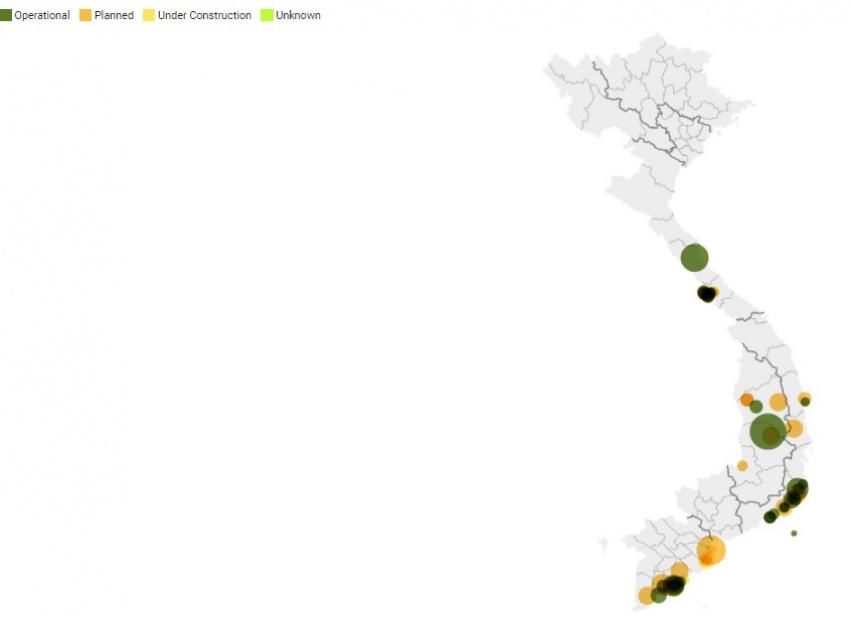

The final version of PDP8 raised the target for solar and wind to 50% of Vietnam’s power supply by 2045. Because wind and solar are intermittent, 18 GW of wind is needed by 2030 and an estimated 42.7 GW of onshore wind and 54 GW of offshore wind by 2045. This rapid expansion is technically feasible: Viet Nam has at least 24 GW of high-quality onshore wind potential with average wind speeds of over 6 m/s, and an additional 404 GW of potential at lower wind speeds of 5-6 m/s. By virtue of its long coastline and exposure to the strong winds of the north-east monsoon, the World Bank estimates Vietnam’s offshore wind potential is more than 500 GW, and could eventually provide the base load that coal currently provides. But taking advantage of this potential will require massive investment as Vietnam’s current wind power comes to just under 4 GW.

Map of Vietnam’s wind potential and/or map of existing wind capacity:

Photo: Map of wind projects in Viet Nam © the Stimson Center

Photo: Map of wind projects in Viet Nam © the Stimson Center

Although solar has driven Vietnam’s recent surge in renewable energy, government interest in wind power actually pre-dates solar. Viet Nam’s PDP7 published in 2010 aimed for 1,000 MW by 2020 and 6,200 MW by 2030. In June 2011, the Prime Minister’s Decision 37 introduced a guaranteed feed-in tariff (FIT) for wind of $0.078/kWh for a 20-year contract.

However, investment in wind power projects has been slow to materialize. Only 135 MW of wind power was online by 2015, well under half the PDP7 target for 2020. In response, Vietnam’s revised PDP7 in 2016 reduced the wind target to 800 MW by 2020. This contrasted with solar, where capacity expanded exponentially after an attractive FIT was announced in 2017.

In the early 2010s, Viet Nam was setting similar wind targets as Thailand and the Philippines but installed capacity lagged both. A key difference was the lower FIT: the Philippines’ FIT was $0.16/kWh and Thailand’s FIT was $0.15/kWh. These higher FITs were successful in stimulating investment. Vietnam’s was simply too low, especially given high interest rates for renewable energy projects.

Infographic: https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/oSjnD/1/ or https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/o24TO/1/

In 2018, Decision 39 raised the wind FIT to $0.085/kWh for onshore and $0.098 for offshore wind for projects that came online by November 1, 2021. This attracted investment: Vietnam’s wind capacity rose 10-fold from less than 300 MW in 2018 to 3,980 MW by November 2022.

Annotated Infographic on Wind Power in Viet Nam: https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/6XDmJ/2/

Photo: An offshore wind power of Trung Nam Group in Tra Vinh Province © Trung Nam Group

Photo: An offshore wind power of Trung Nam Group in Tra Vinh Province © Trung Nam Group

Another 37 projects with 2,500 MW of capacity missed the late October 2021 deadline. In many cases this was attributed to supply chain and labor disruptions as well as commissioning delays due to the COVID pandemic. Although close to completion, these projects are stuck in limbo, as the developers cannot move forward until they know the pricing structure.

As of mid-2022 there is still significant uncertainty about the future pricing structure for both onshore and off-shore wind. Decision 39 indicated that the FIT might be replaced by a reverse auction system after the FIT expired in 2021, which would push investors to compete on price. A recent letter from the Ministry of Industry and Trade proposed FITs that would declines over time through 2023 but no decision has been made. This lack of clarity about the price and PPA terms will likely inhibit further near-term investment.

Another barrier is grid integration. The rapid expansion of solar and wind is straining the electricity grid. The sheer number of new projects that have come online since 2020 have outpaced the ability of the grid to integrate them, particularly in provinces where large amounts of solar and wind are concentrated. About 75 wind plants came online in 2021 alone, and in 2020 more than 100,000 rooftop solar installations and at least 15 solar plants were connected to the grid. Transmission lines often hit full capacity and many projects have suffered curtailment. As a result, in 2022 the National Load Dispatch Centre announced that it would not approve any new wind or solar projects in 2022.

Viet Nam must address grid integration to ensure continued progress toward its COP26 commitments. Even as it pauses new wind and solar, the government needs to invest heavily in improved transmission and, when it becomes economically viable, storage. It also needs to provide clarity on future FITs or reverse auctions. This will be instrumental to maintaining a healthy project pipeline.

Historically, EVN, the state-owned utility, has maintained a monopoly over power transmission. It has also invested heavily in power. As a result, it has limited funding to alleviate the grid bottlenecks that are limiting solar and wind expansion. EVN can work with international funders such as the Development Finance Corporation, Japan Bank for International Cooperation, and Export Finance Australia to build out Vietnam’s transmission system to manage higher amounts of variable energy. Grid constraints brought solar and wind development in Viet Nam to a standstill in 2022. Viet Nam can take advantage of major new funding sources to alleviate this bottleneck, maintain its widely admired renewable energy transition, and avoid similar future challenges as it races towards net zero carbon emissions.

This is part four of six web stories produced by the Stimson Center and IUCN under the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation BRIDGE (Building River Dialogue and Governance), a global hydro-diplomacy project that IUCN is facilitating in 15 transboundary river basins, including the Mekong. For the other five webstories, please see:

#1: Vietnam’s COP26 commitments: a moment of truth

#2: The Sekong A dam in Lao PDR and the Mekong Delta: a moment of decision for Viet Nam

#3: Unlocking international finance for Vietnam’s renewable energy transition