People and species living in drylands have adapted over millennia to cope with extreme climatic variability. Plants and animals such as the African elephant and the Bactrian camel in Central Asia have developed unique physiological and behavioural adaptations. Human populations have similarly adapted management and behavioural strategies that enable them to use highly variable resources.

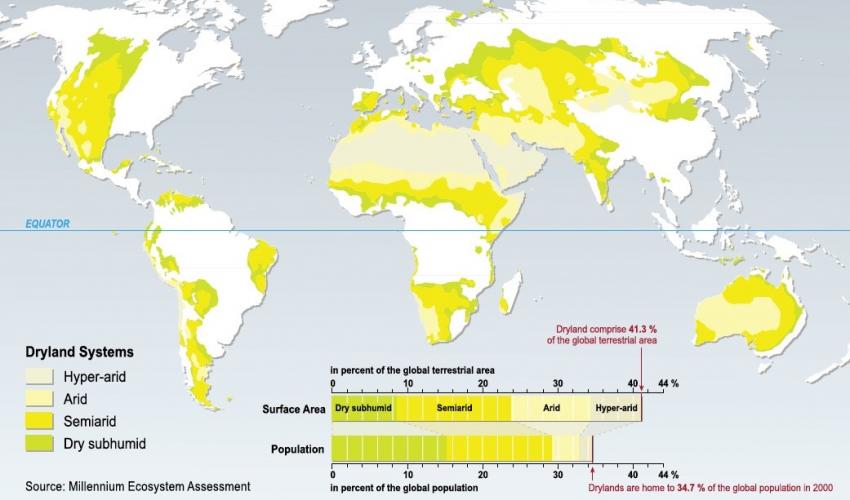

However, climate change is presenting an unprecedented threat to drylands with far reaching environmental, social and economic consequences. Climate scientists predict that global drylands will expand by up to 10% under a high greenhouse gas emission scenario by the end of the21st century, with as much as 80% of this expansion occurring in developing countries.

The dramatic shifts in rainfall patterns caused by climate change are expected to affect both the quantity and distribution of water. Loss of vegetation could lead to the hardening of the soil surface, increased water runoff and consequently reduced ground water recharge. The frequency and intensity of droughts are also expected to increase with climate change. This is of particular concern in drylands, where species and communities already have to cope with dramatic climatic variations.

Climate change is likely to accelerate land degradation, referred to in drylands as desertification. Land degradation is defined as a loss of the ecological and economic productivity of land.

About 20-35% of drylands already suffer some form of land degradation, and this is expected to expand significantly under different emission scenarios. Soil erosion is one of the more significant causes of land degradation in drylands, resulting in the loss of soil organic carbon present in roots and woody components of the soil, and the subsequent loss of land productivity.

Converting dryland areas to other uses, especially to cropland, can also cause land degradation. This can result in the loss of up to 60% of soil organic carbon below ground, and up to 95% of above-ground carbon. These losses contribute directly to greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere, and reduce the capacity of drylands to sequester carbon.

Due to the biophysical, socioeconomic and cultural uniqueness of species and people living in drylands, they remain poorly understood and continue to be dominated by inappropriate investments and land management practices that contribute to further degradation. This increases the vulnerability of drylands to environmental shocks including climate change.