Tourism development in Viet Nam: Boom and Bust?

Viet Nam, with its picturesque landscapes and vibrant culture, has emerged as a popular tourist destination in recent years. Between 2015 and 2019, the number of international tourists visiting Viet Nam surged from 7.9 million to 18 million a year1. However, the rapid pace of development at some of its iconic sites is raising concerns about the long-term sustainability of the tourism industry.

This article examines the impacts of tourism in two of Viet Nam’s most popular destinations, Phu Quoc and Ha Long Bay. Comparisons are drawn with similar cases in The Philippines and Thailand, where popular tourist destinations had to been closed to allow them to recover.

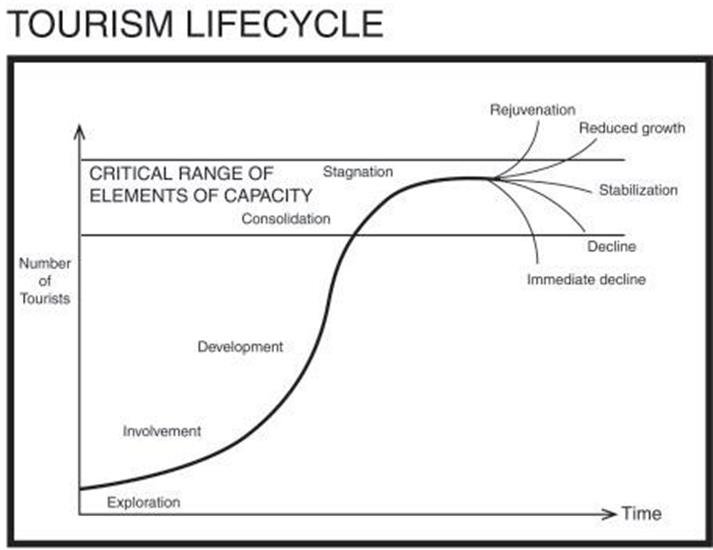

This “boom and bust” pattern is shown in a model proposed by Professor Richard Butler in 1980. According to this model, destinations go through a series of stages, including exploration, involvement, development, consolidation, stagnation, and decline, as they evolve and mature. In essence, Butler warns that tourist sites have the propensity to self-destruct if not well managed.

Increasing evidence suggests that Phu Quoc, Ha Long Bay, and several other sites in Viet Nam have reached the stagnation stage, with the potential for significant declines in high-paying international visitor arrivals.

Photo: The “boom and bust” pattern proposed by Professor Richard Butler © Butler 1980

Photo: The “boom and bust” pattern proposed by Professor Richard Butler © Butler 1980

Fifteen years ago, Phu Quoc was virtually untouched but has since been transformed by resorts, roads, and one of the world’s longest cable cars. The problem is not the new infrastructure per se; rather the absence of accompanying environmental regulations and investments.

In line with their own corporate policies, some hotels implement stringent recycling and energy efficiency standards. But these “islands” of high-performance cannot offset poor environmental management elsewhere. There is nothing hotels can do when trash piles up on the beaches overnight to the horror of their guests. According to the Phu Quoc District People’s Committee, on average, the island generates about 180 tons of waste every day2. Most of this ends up in a huge landfill in the north of the island. The island plans to get rid of this landfill by burning 200,000 tonnes of waste at a cost of VND55 billion (US$2.3 million)3.

Photo: A landfill in Cua Duong Commune in Phu Quoc Island off Vietnam's southern coast © VNExpress

Photo: A landfill in Cua Duong Commune in Phu Quoc Island off Vietnam's southern coast © VNExpress

As is so often the case, the question isn’t conservation vs. development, it’s high-quality development vs. poor-quality development. And the problem isn’t lack of technology or finance. Tourism in Phu Quoc generates hundreds of millions of dollars a year in tax revenue. The decisions are essentially political. When a manager of a 5-star resort was asked if he should meet with the district government to discuss the existential threat to his business posed by marine plastics, he replied “What’s the point? No one cares.”

But people do care. Nine of the 10 most recent TripAdvisor reviews of Phu Quoc’s Bai Tam Sao beach describe the area as “full of rubbish”, “dirty” and “mismanaged”. This is having an impact on visitation. In May 2023, the Kien Giang Province Department of Tourism announced the suspension of all international flights to Phu Quoc due to low demand4. While officials blame this decline on the global economic situation, it is likely that pollution has made things much worse.

Ha Long Bay, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, faces similar problems.

In 2020, it was estimated that Ha Long Bay produces about 28,000 tonnes of plastic waste a year, out of which 5,000 tonnes end up in the sea5. The accumulation of plastic waste, untreated sewage discharge, and industrial pollution has triggered an online backlash. TripAdvisor reviews label the bay as “spoiled” with “oil slicks everywhere” and should be “boycotted”6. Social media is arguably accelerating the Butler model: increasing visitation during the “development” stage, and having the opposite effect when pollution directly impacts the visitor experience, as is now the case.

Experience from The Philippines and Thailand is instructive. In 2018, Thailand closed Maya Bay in Phi Phi Islands due to damage caused by over-tourism. The Philippine government temporarily shut down Boracay Island for the same reason. These closures have allowed the coastal ecosystems to recover and for large investments in water and solid waste management infrastructure.

Why is Viet Nam struggling to cope with the negative impacts of tourism? One way to understand this is through what political economists call the “collective action problem”. This refers to a situation where individuals or groups face a conflict between their personal interests and the collective interest. It occurs when people hesitate to contribute to a common goal (such as reduced pollution) because they anticipate that others may not do the same, leading to a worse outcome for everyone.

Overcoming the collective action problem requires building strong institutional frameworks, bolstering collaboration between stakeholders, and promoting awareness of the consequences of pollution. In the case of Phuc Quoc and Ha Long Bay, it requires government to ensure that investments in essential solid waste management infrastructure are made and that environmental regulations are consistently enforced.

In Phu Quoc and Ha Long Bay, local authorities could require hotels to install “closed loop” water management systems or ban single-use plastic bags and enforce strict waste separation at source, which would greatly reduce solid waste generation. It may also be necessary to reduce visitor numbers based on an objective assessment of the site’s carrying capacity.

But none of these solutions will happen at scale without government leadership. This is what will determine if these sites follow the Butler trajectories of “rejuvenation” or “decline”.

Disclaimer

Opinions expressed in posts featured on any Crossroads or other blogs and in related comments are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of IUCN or a consensus of its Member organisations.

IUCN moderates comments and reserves the right to remove posts that are deemed inappropriate, commercial in nature or unrelated to blog posts.