Adapt or die: lessons from Vulture Conservation in South Asia

For SOS Grantee Ananya Mukherjee, switching from dipstick technology to GPS-enabled bird-tagging was a classic case of adaptive management. Indeed it was one that allowed the larger vulture conservation project to continue working towards its objective: creating three effective Vulture Safe Zones (VSZs) on the Indian subcontinent.

Imagine you are an Indian vulture conservationist with a plan. That plan involves creating Vulture Safe Zones and then ensuring they remain safe enough so that one day vultures could be reintroduced to resume their role en masse as nature’s clean-up crew.

But what happens when things don’t go according to plan? Drawing inspiration from nature, one might say “adapt, or die”!

Vulture Safe Zones are 30,000 sq km areas, declared free from the drug diclofenac. Historically used to treat sick farm animals, diclofenac was also found to be highly poisonous for vultures, especially the Gyps vulture species endemic to the South Asian region.

Since the 1990s Indian vulture populations have plummeted by 97%. Thus, ensuring diclofenac was absent especially from the food supply of the vultures - including the cattle carcasses that they feed on - was deemed critical to the birds’ recovery prospects.

While illegal for veterinary use in India, diclofenac is cheap and still widely available for human consumption making it a slow and difficult process to encourage switching to safer more expensive options like meloxicam.

Progress was slow but steady thanks to the coordinated efforts of the SAVE program: Saving Asian Vultures from Extinction.

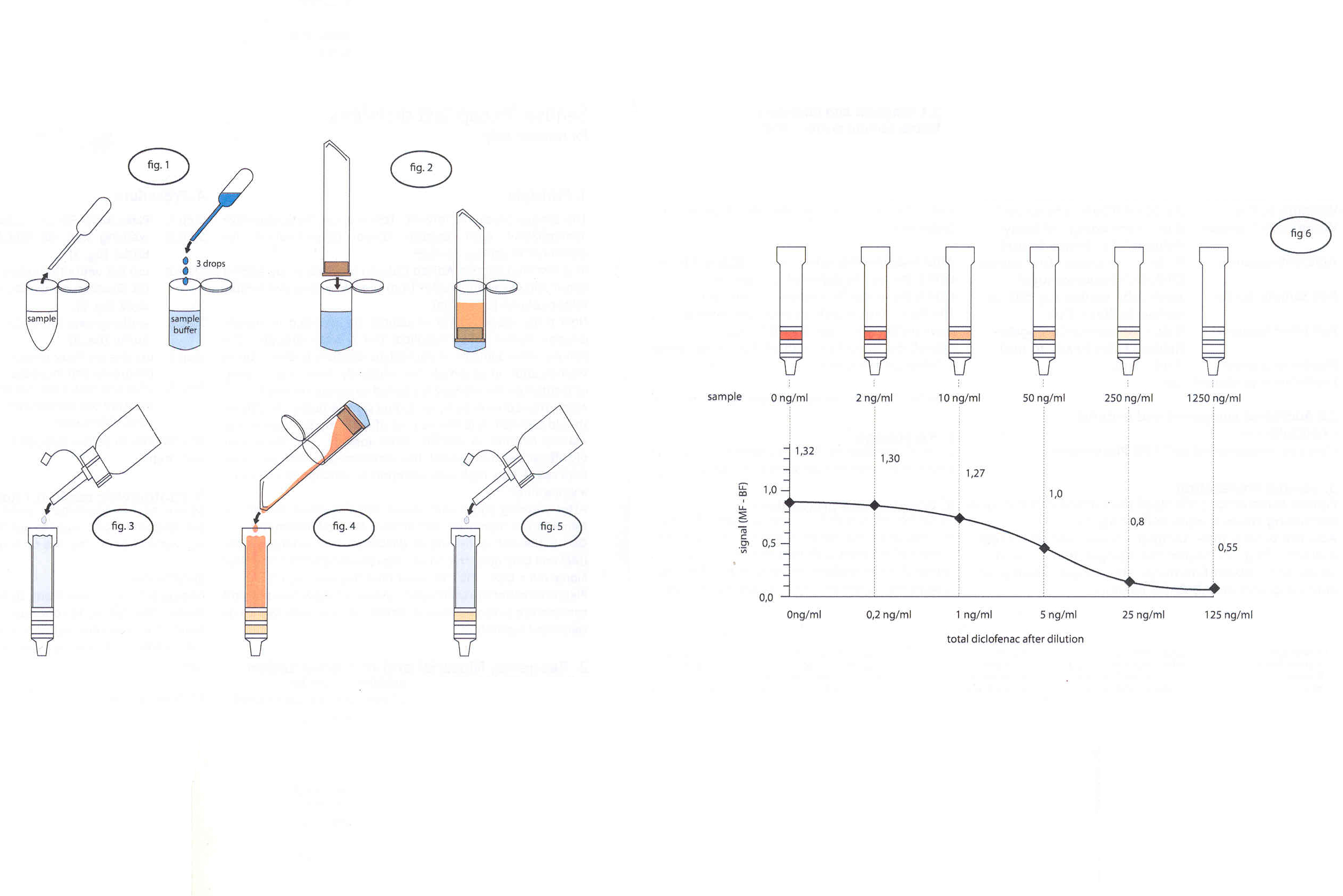

In tandem with the process of creating VSZs in consultation with various stakeholders, SOS Grantee RSPB and partners intended to use an innovative technology – a dipstick - to detect the presence of the drug diclofenac in the carcasses of dead cattle in VSZs, upon which vultures often feed. But test results were less than convincing.

Because the tools proved to be less than reliable, it became impossible to know if diclofenac was present or absent. Thus the likelihood of success in reintroducing the birds in the future became much less certain.

“In conservation you just cannot predict everything” Ananya stresses as she recounts reacting to the discovery mid-way through the project.

Having evaluated a number of options, the project team decided the only way to infer if diclofenac was present was to directly monitor the presence and health of vultures in the designated VSZ’s, using satellite tagging for a selection of birds instead.

Satellite tagging would allow the team to track bird movements and development within the VSZs. But tagging wild birds is not an ideal solution either. It is an expensive technology and tagging requires government permits.

“Consequently we need to be confident that the VSZs are actually safe enough before we start tagging”, Ananya explains. Making VSZs safe depends on effective awareness raising and advocacy work. Based on her success so far, Ananya has also recently published an article in the Bombay Natural History Society’s journal Mistnet, titled “Vulture Safe Zones to save Gyps Vultures in South Asia”

Essentially, the advocacy work involves steadily engaging with multi-level stakeholders to incorporate VSZs in environmental planning while promoting the use of meloxicam.

Meanwhile periodic pharmacy surveys are conducted every year to track the trend in diclofenac sales and indicate whether the message to retailers and farmers alike is being acted upon: choose meloxicam; the vulture-safe alternative.

Based on the progress to date Ananya hopes to tag a few birds in 2015 in Haryana and Assam and later in Uttar Pradesh, with the other states to follow later.

This is a significant step considering “three different states means four different VSZs because of four different socio-political dynamics”. That little detail is not going to stop Ananya Mukherjee from reaching her goal, however.

Help SOS Protect More Species

Protecting threatened species is critical because we are protecting parts of our life support system. Wildlife and nature supply us with so many basic necessities from food to fuel and shelter, but also inspiration in art, language and design to name but a few examples. Right now we are protecting more than 200 species please contribute to SOS to help us continue to protect more of our natural heritage.