These innovative cases are examples where communities have resisted externally-dominated processes and worked together to take back power and control over their territories and the ecosystems with which they have an intimate bond and cultural connection, and at the same time have generated positive biodiversity outcomes.

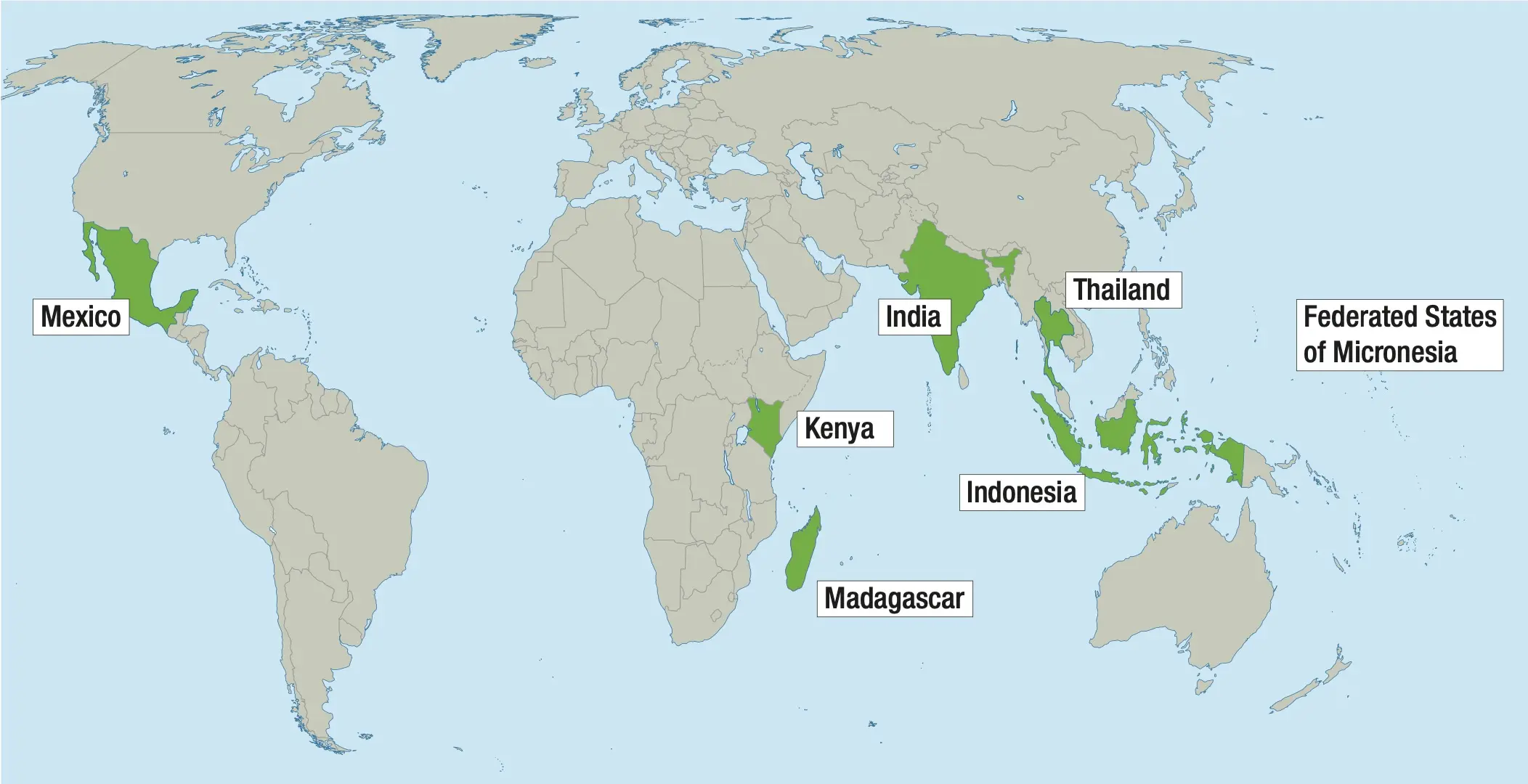

The articles cover a variety of social, environmental, and political contexts and capture very different paths toward more equitable and effective conservation. The cases from Madagascar, Indonesia, and India involve existing externally-driven conservation initiatives, where the state agencies and non-governmental organisations in control were forced to respond to local resistance. For example, the Periyar Tiger Reserve case details how steps were taken from the mid-1990s to move away from an exclusive colonial and post-colonial protected area management style by resolving long-term conflicts, with the state building trust and partnerships with local communities. Over time, this shift led to greatly improved forest quality and increasing populations of key species, notably tigers, to transform Periyar into India’s most effective tiger reserve according to recent national assessments.

In the cases from Mexico and Thailand, the externally-driven commercial exploitation of resources in those ecosystems created ecological degradation to such an extent that communities mobilised to realise alternative forms of governance that improved social and ecological outcomes. For example, in Phang Nga Bay, Thailand, restoration efforts covered more than 25,000 ha of degraded mangroves in the aftermath of destructive commercial aquaculture, through the network of locally-managed marine and coastal areas, with clear benefits for multiple marine species and coastal communities.

The remaining two cases differ in that they involve communities that had maintained comparative autonomy - in Ulithi Atoll, Yap (Federated States of Micronesia), and the primarily Indigenous Maasai communities in the rangelands of Kenya’s Southern Rift Valley. In the face of external pressures on Indigenous governing processes, and consequently the ecosystem’s health, both communities countered pressures by revitalising and adapting their knowledge and customary institutions to better suit changing circumstances. For example, in the Kenyan case, communities resisted pressure to allow tourist lodges to dictate seasonal grazing patterns (as is the case in most conservancies across the region), and prioritised their pastoralist livelihoods by maintaining access to areas providing grazing during times of drought. This was invaluable for the resilience of the community, while the traditional, communal rangeland management also resulted in positive trends and high densities of large mammal populations.

Taken together, the seven cases represent the frontline of struggles for the future of critical biodiversity and habitats. All of these cases have, at their core, the well-being of the communities, which is intimately tied to the health of the ecosystems, and demonstrate the contemporary relevance of the knowledge and cultural resilience of Indigenous peoples and local communities.

The cases demonstrate that for improvements in conservation to be realised at the site level, the implementation of social objectives must extend far beyond the provision of compensation or support for income generation, to also address trust and relationships, recognise diverse worldviews, place-based connections to nature, tenure security, and the cultural values and practices which coalesce in strong local and customary institutions.

The cases highlight the importance of women and youth as essential in revitalisation processes and decisions, and the importance of their holding key roles that see them shape community organisations and strategies.