The light in the forest: A lesson in optimism from conservationists in Brazil

CEESP News - by Lydia Cardona, Manager, Center for Communities and Conservation at Conservation International

An innovative workshop on conflict sensitivity and conflict transformation was held in Brazil in February. Supported by PeaceNexus Foundation, the workshop centered around discussing and responding to conflict within environmental conservation approaches in the Amazon.

Focusing on Peace Circles and conflict analysis, Conservation International members and partners transformed their worldview, finding ways to encourage one another by sharing struggles, amid the backdrop of the threats from forest fires and political and social unrest.

Just a few months ago, the world stirred to action over a surge in forest fires in Brazil, Peru, Bolivia and Paraguay.

The Amazon rainforest—the planet’s lungs—was burning.

This incredible remote forest plays a critical role in global climate regulation (and much more); its benefits transcend boundaries and politics. And it faces existential threats of a scale typically depicted in epic blockbuster films: Deforestation. Fires. Murder. Cue media images of a handsome yet nefarious despot who—empowered with support from a populace fed up with corruption—stands self-assured while juxtaposed with representatives from private corporations clamoring for the bountiful wealth to be made in the untapped jungle.

Photo: Lydia Cardona

Photo: Lydia Cardona

Despite the lure of economic growth, most of this wealth will remain concentrated in the hands of the wealthy. Expansive soy plantations, which comprise around 37 million hectares of land in Brazil, require limited on-hand labor thanks to automation—meaning few economic opportunities for the rural poor associated with soy expansion. As agribusiness continues to grow in Brazil, vulnerable local communities who depend directly on the forest for their livelihoods are left facing the lawlessness, insecurity, and encroachment that accompany the deforestation.

Today, the plot continues to thicken. In the absence of an otherworldly Avenger to intervene against evolving dangers and injustices, a key question emerges: How do you maintain hope in times of darkness?

This question was not the explicit focus of a recent workshop on conflict sensitivity and conflict transformation, hosted by CI Brazil on February 3-6 with support from Conservation International’s (CI) Center for Communities and Conservation. But given the theme, it emerged naturally as a strong undercurrent. The workshop brought together CI staff and local partners from throughout the Amazon region with a two-fold aim: to discuss how conflict affects environmental work in the region and to learn skills for responding to these challenges. Skills building over the course of the workshop focused specially on conflict analysis, an approach for understanding conflict challenges more deeply, and Peace Circles, an approach for transforming them.

Photo: Lydia Cardona

Photo: Lydia Cardona

For environmentalists working in this context, the threats are persistent. This is no new phenomenon: for decades, the names of environmental defenders and indigenous advocates—many silenced permanently for their advocacy—have been emerging from this region. Working in the Amazon has always meant treading carefully, as it seems nearly everyone has some interest in the vast natural wealth of the forest. Yet treading carefully is becoming increasingly impossible given the government’s framing of environmental justice and conservation as mutually exclusive to development—environmental stewardship is not apolitical. And so, over the four days of the workshop, participants emerged lighter each day as the stories of despair and hope bubbled up. Many centered on the challenges of advancing a sustainable vision for the Amazon where both people and nature prosper, and many others on the life and death struggle of pursuing this work.

One such story was that of a woman from Santarem who has served in many leadership roles during her struggle against large-scale soy expansion in the region. She recalled that, as a union leader advocating for rural workers’ rights, she was routinely under threat. Initially, she refused police protection, determined as she was that these threats do not deter her fight for justice. Relentless in her efforts, she ignored one warning to avoid an event where she was scheduled to speak. Hired gunmen, she was told, were coming for her. She attended the event as planned but left early to heed some caution. Shortly after her departure, gunmen stormed the gathering in search of her. She was nowhere to be found, so they left behind a dire warning: they burned down the homes of 25 workers from the gathering.

Photo: Maria Farias

Photo: Maria Farias

Participants break the peace circle to show support to local activist after she shares her emotional story. Photo credit: Maria Farias

While recounting this experience, she noted with deep regret how she had been willing to accept the personal costs of this struggle but never imagined that it could ultimately be borne by those she had intended to help. This and many other stories emerged throughout the workshop, setting an austere yet contemplative tenor for the first few days. As one workshop participant noted, “there’s a sense of urgency” to the challenges they face and their outcome. Yet despite the gravity of what lay ahead, the collective mood was one of promise. Perhaps it was only natural that such a group, whose regular encounters with the waves of despair and persistence, would emerge from these discussions with a lightness and defiant hope. Perhaps still it is that the format of the workshop—engaging through a Peace Circle—enabled this to emerge.

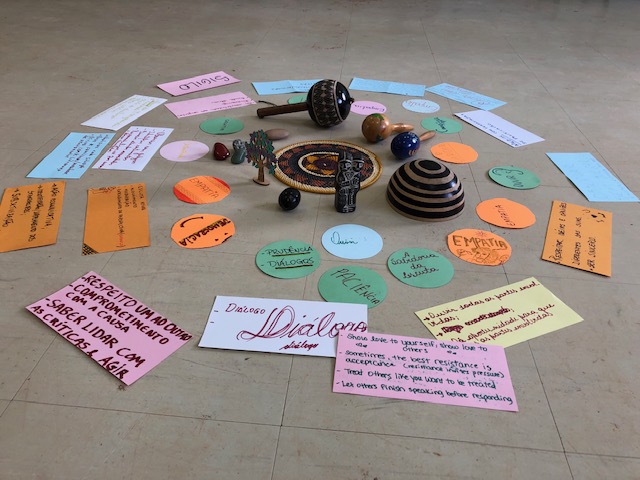

With roots in indigenous restorative justice practices, Peace Circles—also known as Peacemaking Circles—aim to bring together victims, offenders, and generally anyone impacted by a transgression to sit, share, listen, and collaboratively develop solutions to resolve conflict and heal its harm. The guidelines for interaction, which encompasses the use of a “talking piece” that affords authority to a single person to speak at a time, ensure that there is no hierarchy in this process. Everyone has equal value and equal space to speak, and everyone must listen. The approach compels participants to see each other as human beings and address the issues that really matter—ones often buried deep beneath the surface. Given its focus on sustainable, transformative outcomes, the process can take weeks or months. While the aim is to generate collaborative, creative solutions, the process often leads to a sense of healing from grievances and mended relationships.

In the Brazilian Amazon, rife with conflict, violence, and structural inequalities, this approach has shown great potential as a tool for conflict transformation. Kay Pranis, the author who popularized this approach, saw the potential for its uptake in Brazil and freely offered the seeds it would need to flourish: she released the Portuguese translation of all her texts in Brazil without copyright. This means anyone can access this knowledge online and put it to practice. Already, dozens of judges have been trained in this methodology. Our own workshop facilitator, Professor Nirson Medeiros da Silva Neto, has spent years applying this approach towards resolving environmental conflict in the region.

And so, over the final two and half days of the workshop, the group of 20 participants sat in a circle and passed around the speaking piece—a decorative bowl made from dried gourd, symbolic of the indigenous communities of the Amazon—in response to key questions posed by Professor Nirson. The purpose was to learn about this approach through experiencing it. Yet there was nothing procedural about this curriculum. One by one, each person shared stories and struggles from their work, purging a weight carried deep within and creating space for lightness and hope.

Over the four days, acknowledging the enormity of the challenges and the personal costs of this struggle, was a key benefit of the circle process that created a sense of motivation for generating solutions. The group emerged from the workshop with an eagerness to practice new skills, but more importantly, they appeared emboldened to take on the tasks ahead.

As the world’s attention has redirected to a global pandemic seemingly drawn from yet another blockbuster, the burning of the Amazon is no longer on people’s minds. But the challenges in this region persist and may perhaps only escalate in this crisis. Indigenous communities are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of COVID-19. The absence of forest patrolling and monitoring during this time of quarantine has inspired increasing bluster among actors seeking to take advantage of the crisis to seize new swaths of forest. Now more than ever, the stakes are highest just as the need for hope is greatest.

For me, the February workshop with CI staff and partners is a living demonstration of how light illuminates, shadows define. The hardships many of these environmental advocates encountered have sharpened their vision of hope and forged a unique strength for the journey ahead. The four days of the workshop became of process of homing in on and uncovering how these strengths make them distinctly equipped with solutions for their context, engendering a renewed sense of hope and lightness. “We cannot forget that we have the answers to these challenges”—expressed Isabel Moura, a law student trained in the practice of peace circles— “We may get frustrated, but we cannot become paralyzed.”

It is a one-foot-at-a-time mentality for a goliath problem, yet it stands the best chance at creating meaningful change. And so, they persist in their efforts, even at great personal risk. In place like the Amazon, where life often unfolds through events that seem like scenes from a blockbuster, one thing is clear: no masked superhero holds a candle to these real-life protagonists.

Photo: Lydia Cardona

Photo: Lydia Cardona