Privately protected areas: advances and challenges

Protected areas exist under a range of governance types. However, those run by private entities (non-profit organisations, for-profit organisations and individuals) have not always received much attention from the international community. These areas are collectively known as privately protected areas, or PPAs. Unlike broader terms such as ‘private conservation initiative’, the term ‘PPA’ indicates adherence to the IUCN definition of a protected area. Despite this, PPAs are reported to the World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA) by only 27 countries and territories, with 99% of records confined to just nine countries.

Red Kangaroo (Macropus rufus) at Neds Corner Station, a 300 km2 former grazing property in the state of Victoria, Australia, now owned and run as a PPA by the Trust for Nature

Photo: James Fitzsimons

While under-recognition remains a problem, there have been a number of recent advances in thinking around PPAs, including the publication of new IUCN guidance, the development of supportive national and international policies, and the implementation of measures to improve documentation. These advances are the subject of a recent paper in the latest issue of the Parks Journal, which also discusses associated challenges and opportunities for the future.

Advances in how PPAs are recognised, supported and documented are important because PPAs have the potential to help address a range of conservation challenges. By acting as components of broader protected area networks, PPAs can contribute to the connectivity and ecological-representativeness of the conservation landscape. Private actors may also be capable of extending protection to lands or waters that governments are unable to acquire, and adapting their management approaches more rapidly than governments in the face of environmental changes, threats or opportunities.

Photo: © Kent Redford

Photo: © Kent Redford

Until recently, discourse around PPAs was hindered by the absence of a globally-accepted definition. Following in-depth consultation, IUCN guidance was published in 2014 that presented a unified definition of a PPA. It also offered advice on how to apply the definition in the face of challenges commonly faced by PPAs. The guidance was followed in 2016 by a resolution of the IUCN World Conservation Congress, which encouraged multiple actors to promote the efforts of private governance authorities. The Convention on Biological Diversity Secretariat has since expressed interest in a systematic collection of information on PPAs.

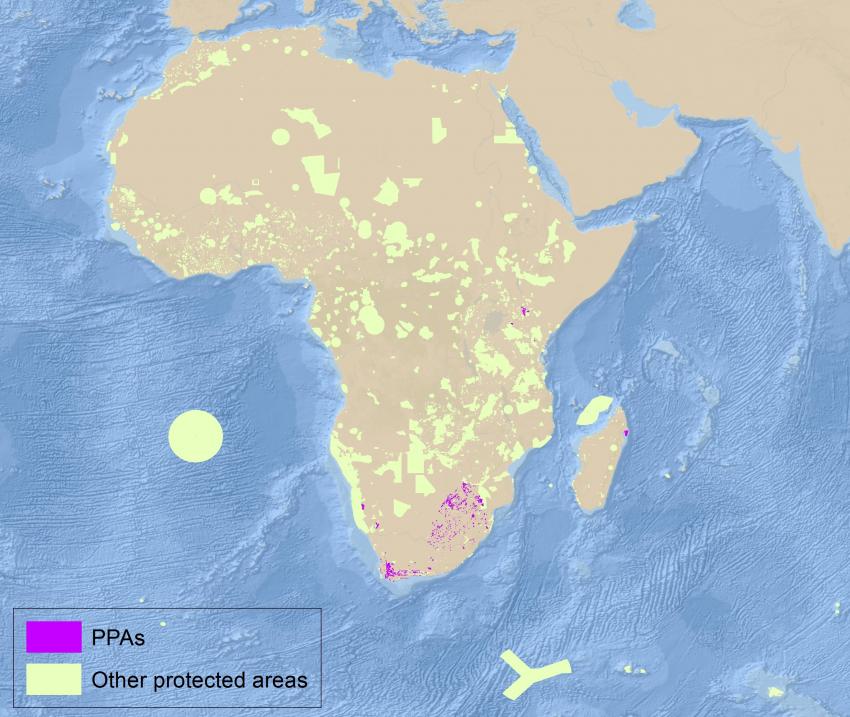

These recent advances at the international level have been matched, in some cases, by developments in national policies. Some countries, such as South Africa, have implemented initiatives aimed at documenting PPAs in order to better assess progress towards conservation targets. Similarly, there has been a concerted effort to map PPAs in the United Kingdom in recent years, led by the IUCN National Committee UK, and involving multiple NGOs and the UK government. These are two examples of a shift in the attitudes of some countries towards greater recognition of PPAs, and their results are clearly visible in the African and Western European maps presented in the Parks Journal paper.

Looking to the future, there are a number of emerging opportunities for PPAs. National-level assessments, such as Putting Nature on the Map, could be more widely applied to document PPAs and identify the best mechanisms to support them. IUCN’s Green List of Protected and Conserved Areas offers an opportunity to highlight excellence in PPA management. In an example of international collaboration, a global network of PPA experts and stakeholders is being built through the IUCN WCPA Specialist Group on Privately Protected Areas and Nature Stewardship. This group is also working to develop best practice guidance on the governance and management of PPAs.

This selection of opportunities demonstrates that multiple sectors have a role to play in supporting PPAs. International organisations, national governments, and PPA governance authorities can all build on recent advances by promoting, recognising and enhancing biodiversity conservation within PPAs.

Article by Heather Bingham, photos by Kent Redford and and James Fitzsimons.

Read the full paper in Parks Journal 23.1: Privately protected areas: advances and challenges in guidance, policy and

documentation

Map: Protected Planet