Deep-sea mining effects may be felt from top to bottom, surface to seabed

Seabed mining effects will probably not be confined to the sea floor, argues a Proceedings of the National Academy (PNAS) journal article from the University of Hawaii, co-authored by IUCN's High Seas Adviser, Kristina Gjerde. The effects will be multiple, and risk affecting marine life for hundreds of kilometres from the site. The scientists submitting the paper urge further, and urgent, assessment of ecological impacts above the sea floor.

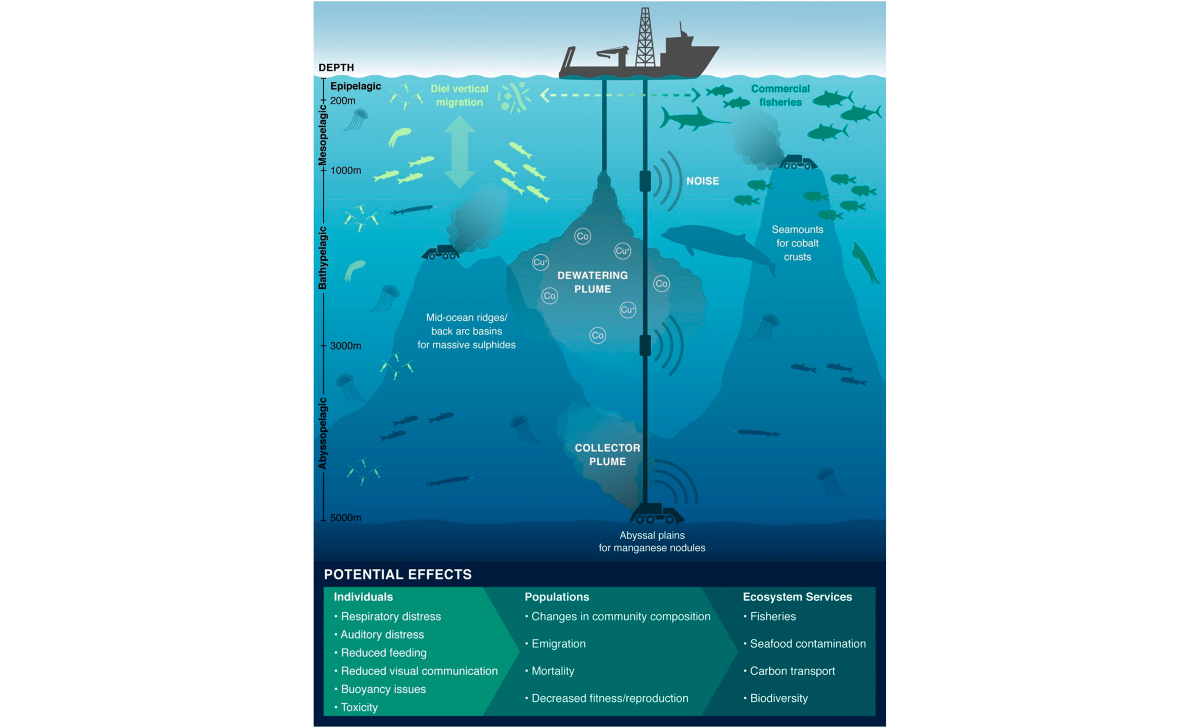

Graphic: Seabed mining effects on water column

Photo: Jeff Drazen

Deep-sea mining activities are anticipated to begin soon for copper, cobalt, zinc, manganese and other valuable metals as interest has grown substantially in the last decade. Most research assessing the impacts of mining has focused on the seafloor. However, a new study, led by University of Hawai‘i (UH) at Mānoa, argues that deep-sea mining poses significant risks, not only to the area immediately surrounding mining operations but also to the water column hundreds to thousands of metres above the seafloor, threatening vast midwater ecosystems.

Encouragingly, these same scientists suggest how these risks could be evaluated more comprehensively to enable society and managers to decide if and how deep-sea mining should proceed.

The deep midwaters of the world’s ocean represent more than 90% of the biosphere, contain 100 times more fish than the annual global catch, connect surface and seafloor ecosystems, and play key roles in climate regulation and nutrient cycles. These ecosystem services, as well as untold biodiversity, could be negatively affected by mining.

Large amounts of mud and dissolved chemicals are released during mining, and large equipment produces extraordinary noise - all of which travel high and wide. Unfortunately, there has been almost no study of the potential effects of mining beyond the habitat immediately adjacent to extraction activities.

Despite this, currently 30 exploration licenses have been granted by the International Seabed Authority (ISA) covering about 1.5 million square kilometres of the seafloor on the high seas (areas beyond national jurisdiction) and added to that, some countries are exploring exploitation in their own national waters as well.

“This is a call to all stakeholders and managers,” said Jeffrey Drazen, lead author of the article and professor of oceanography at UH Mānoa. “Mining is poised to move forward yet we lack scientific evidence to understand and manage the impacts on deep pelagic ecosystems, which constitute most of the biosphere. More research is needed very quickly.

“Harm to midwater ecosystems could affect fisheries, release metals into food webs that could then enter our seafood supply, alter carbon sequestration to the deep ocean, and reduce biodiversity that is key to the healthy function of our surrounding oceans.”

In accordance with UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the ISA is required to ensure the effective protection of the marine environment, including deep midwater ecosystems, from harmful effects arising from mining-related activities. In order to minimise environmental harm, mining impacts on the midwater column must be considered in research plans and development of regulations before mining begins.

Kristina Gjerde, senior high seas advisor to IUCN’s Global Marine and Polar Programme, noted, “First of all we need an improved understanding of the affected deep sea environment and the long term consequences of those changes for ocean health, food security and climate resilience as well as for the fascinating life forms that depend on sediment-free waters to survive.

“This study underscores the need to slow any rush to finalise the ISA’s exploitation regulations.”

Drazen also added, “We are urging researchers and governing bodies to expand midwater research efforts, and adopt precautionary management measures now in order to avoid harm to deep midwater ecosystems from seabed mining.”

This article is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy.