At the UN Convention for Biodiversity’s 15th Conference of Parties (CBD COP15) in Montreal in December 2022, countries are set to agree to a post-2020 UN biodiversity framework that sets concrete, quantifiable goals and targets for the conservation of species, ecosystems and genetic diversity in order to halt the ongoing extinction crisis.

As the world is set to adopt a landmark treaty to halt the loss of biodiversity later this year, implementing and measuring progress against specific goals of this agreement will soon become a focus. With its long history of establishing standards and tools to track and measure the conservation of nature, IUCN offers solutions to this challenge – and one of its most recent publications closes a major remaining gap: the classification and assessment of ecosystems.

Among the most discussed targets in the current draft agreement is the conservation of at least 30% of the world’s land and sea areas through “effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well-connected systems of protected areas.”

Experts hope that this plan, known as 30x30, will contribute to reaching the long-term goals of increasing by at least 15 per cent the area, connectivity and integrity of natural ecosystems, reducing the rate of extinctions at least tenfold, and halving the risk of species extinctions across all taxonomic and functional groups by 2050.

These ambitious goals will require bold, transformational, collective action from all sectors of society. To achieve them, governments, businesses and civil society will need the ability to prioritize ecosystems, places and interventions to halt declines in biodiversity; to measure, monitor and report on progress; and to adjust strategies accordingly. Providing tools that make this possible has long been one of IUCN’s key strengths, and our latest contribution, the IUCN Global Ecosystem Typology, closes one of the major remaining gaps - Jane Smart, Head of IUCN’s Centre for Science and Data.

Led by Professor David Keith of the University of New South Wales in Sydney, experts in the IUCN Commission on Ecosystem Management have developed the first universal, comprehensive typology of Earth’s ecosystems on land, in freshwaters and oceans and even below ground.

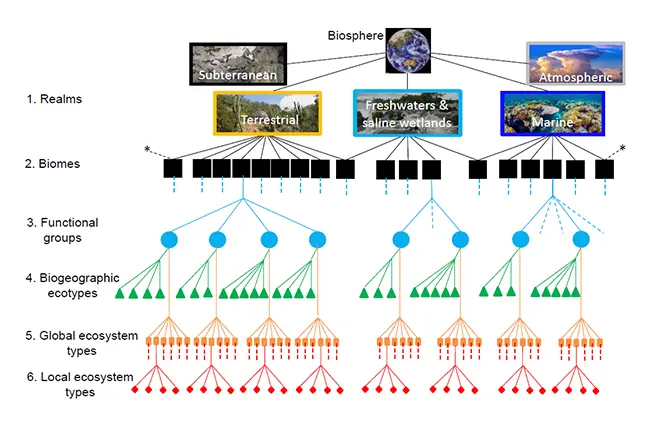

Taking into account their ecological functions as well as the animals, plants, fungi and microorganisms found within them, the framework groups our planet’s ecosystems into four realms, 25 biomes and 110 ecosystem functional groups, which can be viewed here; with further differentiations applied at an even finer scale. The typology includes not only the full range of natural and semi-natural ecosystems, but different types of artificial ecosystems, created and maintained by humans.

The IUCN Global Ecosystem Typology comprises six hierarchical levels.

At the ecosystem level, the IUCN Red List of Ecosystems has been instrumental in framing conservation policies, regulations, legislation and management. Twenty-five countries have applied this tool since its adoption by IUCN Council in 2014, mostly at a national level. The new Global Ecosystem Typology now paves the way for global Red List of Ecosystem assessments, and for neighbouring countries to place the ecosystems within their borders into a broader context for decision making.

Ecosystem inventories based on the Global Ecosystem Typology will also help to advance applications of the universally accepted IUCN Protected Areas categories, together with the IUCN standards for identification of Key Biodiversity Areas and the IUCN Green List of Protected Areas, which provides a benchmark for effective area conservation.

Similarly, the Global Ecosystem Typology can be linked to tools such as the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species and the IUCN Green Status to provide ecosystem information for species’ status and conservation potential; and the Species Threat Abatement Metric (STAR), which helps identify geographical areas where the potential conservation gains are biggest.

With the CBD COP15 approaching, the need for a truly comprehensive global classification of Earth’s ecosystems to guide and measure their conservation has never been greater. Without such a system, how could we ensure that all types of ecosystems are covered adequately by our conservation actions? How would we prioritize action without a tool to determine which types of ecosystems are most at risk, and which ones offer the most important benefits to humanity?

Today, we are a big step closer to answering these questions. While the ecosystem typology was first published in 2020 as an IUCN Global Standard, the authors have now presented the full scientific basis of their work in the journal Nature. In the paper, they demonstrate how the typology allows us to gain a deeper understanding of how different ecosystems function, providing a basis for diagnosing causes of decline and degradation, and for designing and prioritizing actions for protection and restoration.

For instance, the authors were able to draw important insights from the Typology into the expansion of artificial ecosystems such as those in the Intensive land use biome, T7.

Human-created or maintained ecosystems account for about 10% of all ecosystem types, but they are expanding at the expense of natural ecosystems and now cover more than 30% of the world’s land surface. This is concerning, because natural ecosystems support a greater diversity of life, including more than 90% of threatened species, and provide a greater array of ecosystem services that sustain human well-being and livelihoods - Professor David Keith.

Further, the researchers are using the Typology in combination with other databases to analyse which types of ecosystems are under particular pressure, but lack adequate formal protection:

In particular, freshwater ecosystems and temperate forests appear to be among the most degraded and the least protected ecosystem types on earth. When you take into account that these ecosystems produce many services that are essential for human survival, it becomes clear that they require urgent conservation attention - Professor David Keith.

The fact that the IUCN Global Ecosystem Typology enables such analyses is a big step forward – but David Keith emphasises that a lot of important work remains to be done.

Now that we have a robust classification, the next major frontier will be to develop global, comprehensive maps of all ecosystem types that can inform a system to monitor their status and inform decision-making. Many of the world’s 110 ecosystem types are already covered by high quality maps that can be updated thanks to satellite technology, but for others, we still only have rudimentary data.

The IUCN Ecosystem Typology is a milestone towards our ability to measure progress in conservation. It will help inform discussions about the definition and tracking of nature-positive at the IUCN Leaders Forum in Jeju later this week as well as the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework, which is on the agenda in Montreal in December - Angela Andrade, Chair of IUCN’s Commission on Ecosystem Management and a co-author of the Nature paper on the Typology