Surprise species at risk from climate change

Most species at greatest risk from climate change are not currently conservation priorities, finds an IUCN study that introduces a pioneering method to assess the vulnerability of species to climate change.

The paper, published in the journal PLOS ONE, is one of the biggest studies of its kind, assessing all of the world’s birds, amphibians and corals. It draws on the work of more than 100 scientists over a period of five years.

Up to 83% of birds, 66% of amphibians and 70% of corals that were identified as highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change are not currently considered threatened with extinction on The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™. They are therefore unlikely to be receiving focused conservation attention, according to the study.

“The findings revealed some alarming surprises,” says Wendy Foden of IUCN Global Species Programme and leader of the study. “We hadn’t expected that so many species and areas that were not previously considered to be of concern would emerge as highly vulnerable to climate change. Clearly, if we simply carry on with conservation as usual, without taking climate change into account, we’ll fail to help many of the species and areas that need it most.”

Up to nine percent of all birds, 15% of all amphibians and nine percent of all corals that were found to be highly vulnerable to climate change are already threatened with extinction. These species are threatened by unsustainable logging and agricultural expansion but also need urgent conservation action in the face of climate change, according to the authors.

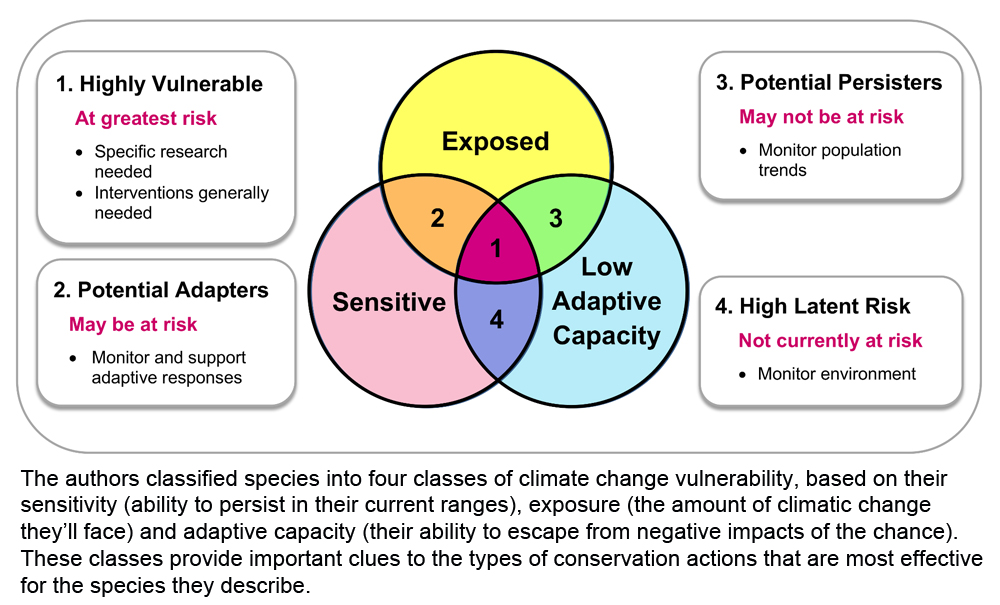

The study’s novel approach looks at the unique biological and ecological characteristics that make species more or less sensitive or adaptable to climate change. Conventional methods have focussed largely on measuring the amount of change to which species are likely to be exposed. IUCN will use the approach and results to ensure The IUCN Red List continues to provide the best possible assessments of extinction risk, including due to climate change.

“This is a leap forward for conservation,” says Jean-Christophe Vié, Deputy Director, IUCN Global Species Programme and a co-author of the study. “As well as having a far clearer picture of which birds, amphibians and corals are most at risk from climate change, we now also know the biological characteristics that create their climate change ‘weak points’. This gives us an enormous advantage in meeting their conservation needs.”

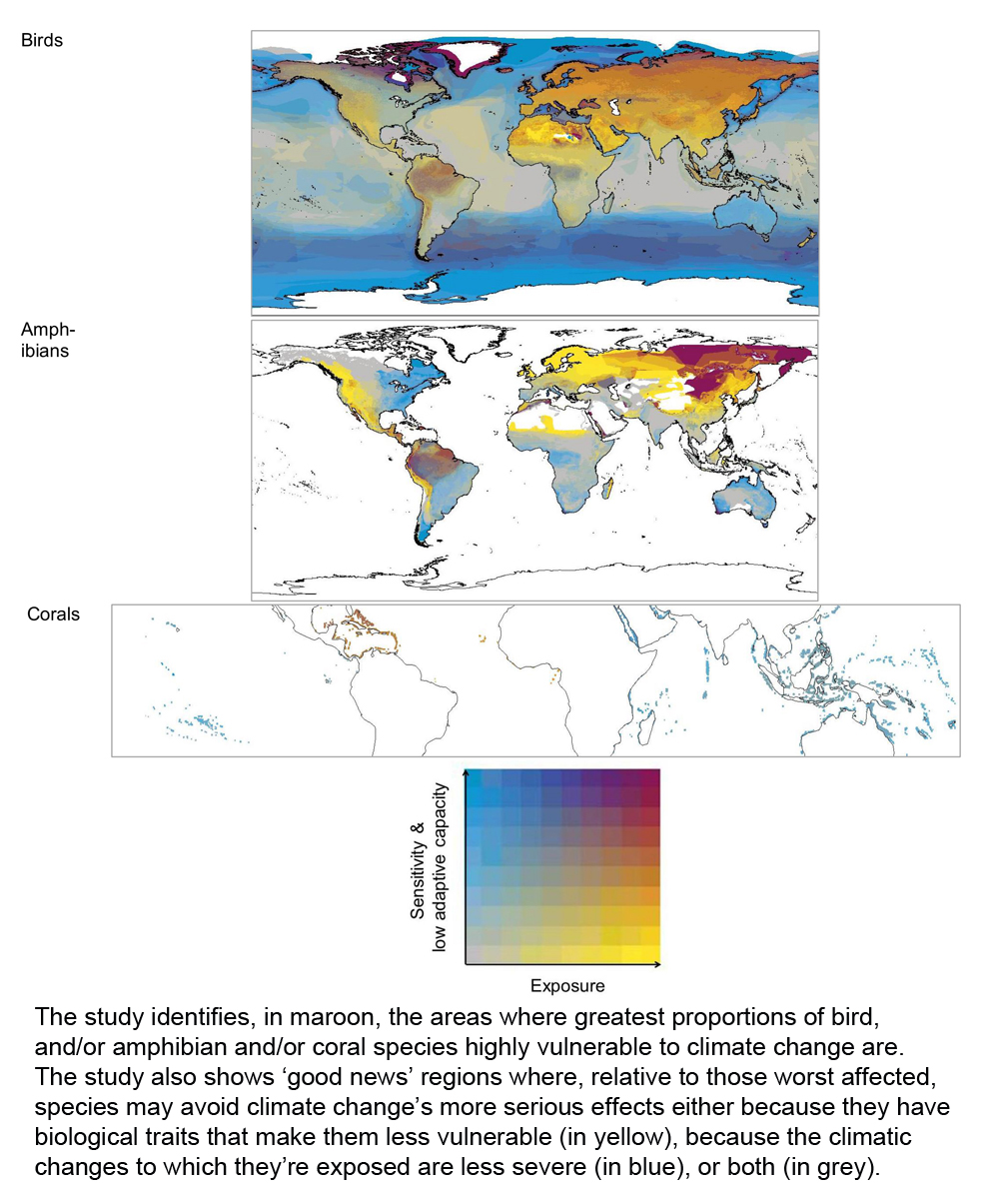

The study also presents the first global-scale maps of vulnerability to climate change for the assessed species groups. It shows that the Amazon hosts the highest concentrations of the birds and amphibians that are most vulnerable to climate change, and the Coral Triangle of the central Indo-west Pacific contains the majority of climate change vulnerable corals.

“Looking into the future is always an uncertain business, so we need a variety of methods to assess the risks we face,” says Simon Stuart, Chair of IUCN’s Species Survival Commission and one of the study’s authors. “This new method perfectly complements the more conventional ones used to date. Where various methods give the same frightening results, then we really need to pay attention and take steps to avoid them.”

The new approach has already been applied to the species-rich Albertine Rift region of Central and East Africa, identifying those plants and animals that are important for human use and are most likely to decline due to climate change. These include 33 plants that are used as fuel, construction materials, food and medicine, 19 species of freshwater fish that are an important source of food and income and 24 mammals used primarily as a source of food.

“The study has shown that people in the region rely heavily on wild species for their livelihoods, and that this will undoubtedly be disrupted by climate change,” says Jamie Carr of IUCN Global Species Programme and lead author of the Albertine Rift study. “This is particularly important for the poorest and most marginalized communities who rely most directly on wild species to meet their basic needs.”

Supporting quotes:

“Both vulnerable species and people will need to adapt to climate change,” says Elizabeth Chadri, Program Officer, MacArthur Foundation, the major funder of this work. “Keeping ecosystems healthy and intact will play a key role in helping human societies adapt to changing climates. By highlighting those species in need of the most urgent attention, the study helps to show the parts of the world where this needs to be focused.”

“We welcome the opportunity to introduce this new approach,” says Georgina Mace, Professor of Conservation Science at University College London and a key investigator for the study. “By including species’ biological traits in assessments of climate change risk, we look at much broader range of possible impacts and hopefully gain a better understanding of how biodiversity will fare under climate change.”

“We cannot afford to be complacent about the study’s results. Highly climate change vulnerable species require targeted action to help them adapt to on-going and future climate, says Stuart Butchart, Head of Science at BirdLife International and a key investigator for the study. “Those that already face high extinction risk from threats such as habitat loss, unsustainable use and invasive species are our most urgent priorities.”

"The wildlife of the Albertine Rift supports millions of people by providing food, medicine, fuel, timber and tradable goods,” says Thomasina Oldfield, TRAFFIC’s Programme Leader on Research and Analysis and project partner of the Albertine Rift study. “Knowing how these species are likely to be impacted by climate change is essential for developing effective climate change adaptation strategies for both people and biodiversity. We hope to be able to roll this approach out in other regions.”

Editors’ notes

The paper, Identifying the World's Most Climate Change Vulnerable Species: A Trait-Based Assessment of all Birds, Amphibians and Corals, and the report, Vital but vulnerable: climate change vulnerability and human use of wildlife in Africa’s Albertine Rift, were funded by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation with contributions from the Indianapolis Zoo.

For more information or to set up interviews, please contact:

Ewa Magiera, IUCN Media Relations, t +41 22 999 0346, m +41 79 856 76 26, ewa.magiera@iucn.org

Lynne Labanne, IUCN Global Species Programme, m +41 79 527 7221, lynne.labanne@iucn.org