The Sekong A dam in Lao PDR and the Mekong Delta: a moment of decision for Viet Nam

This is the second in a series of six web stories exploring how Vietnam can implement its COP26 energy commitments while minimising environmental impacts and making progress on broader sustainable development goals. Other pieces explore topics like how to stimulate international finance for renewables and expanding wind in Vietnam’s electricity mix. This piece explores how Vietnam can protect the natural productivity of the Mekong Delta by investing in alternatives to the Sekong A dam in Lao PDR.

Photo: Sekong river in Cambodia © IUCN Viet Nam

The Mekong Delta, which is home to 90% of Vietnam’s rice exports and most of its fruit and aquaculture production, plays a major role in national and regional food markets. However, the delta’s agriculture and fisheries are threatened by a mix of sea level rise, groundwater exploitation, and the impacts of upstream projects that have diminished the flow of sediment and nutrients from the Mekong River. Without transboundary cooperation on energy planning and investment, there is a risk that Vietnam successfully transitions into renewable energy domestically but still purchases electricity from hydropower projects in Lao PDR that directly threaten the delta.

The Vietnamese-built Sekong A dam in southern Laos, now undergoing preparatory work, is an example of such an undesirable and avoidable outcome. Halting construction of the Sekong A dam would have virtually no impact on regional energy security yet would form part of an energy planning and investment strategy that conserves the economically vital Mekong Delta.

Viet Nam has already acted to reduce domestic threats to the Mekong Delta. In November 2017, the government issued Resolution 120, which provides a legal basis for de-intensifying rice production for multiple social, economic, and climate change adaptation benefits. Resolution 55 was approved in February 2020 and sets out a vision for large-scale integration of renewable energy. While Resolution 55 and Resolution 120 address separate issues, they are connected because the choices that Viet Nam makes in terms of its energy mix can either strengthen or undermine Resolution 120.

Table overview of key points from Resolutions 120 and 55: https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/odCcD/2/

Over 150 dams have been built in the Mekong river basin, including 13 on the mainstream: 11 in China and two in Lao PDR. Most of Lao PDR’ s hydropower is intended for export to neighboring countries, including Viet Nam. As Viet Nam moves to reduce coal in its energy mix and increase power imports from Lao PDR, Viet Nam’s decisions about which power projects in Laos to invest in and buy from will impact sediment flow to the delta and fish migration.

The Sekong A dam will have serious impacts on sediment and fisheries because of its location on the Sekong mainstream close to the confluence of the Sesan and the Srepok rivers. These two rivers were cut off from the Mekong when Cambodia built the Lower Sesan 2 dam in 2018, leaving the Sekong the Mekong’s largest free-flowing tributary and a vital channel for fish migration, spawning, and stock recovery. Recent research shows that following the completion of the Lower Sesan 2, more fish and a larger number of species are migrating up and down the Sekong. Since half the fish caught in the Mekong are long-range migrants, maintaining the Sekong as free-flowing is vital to regional fisheries and food security.

Sekong A dam and Connectivity: https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/qfJmB/1/

Photo: Sekong A dam satellite image © Planet Labs, Inc

Photo: Sekong A dam satellite image © Planet Labs, Inc

If built, the Sekong A dam would produce just 86 MW, a tiny fraction of electricity relative to regional power supply. Yet it would disconnect all but 126 km of the Sekong’s 1,917 km from the Mekong, further restricting sediment delivery to the delta thereby threatening the success of Resolution 120. It would also gravely weaken Vietnam’s widely admired leadership on sustainability regionally and globally.

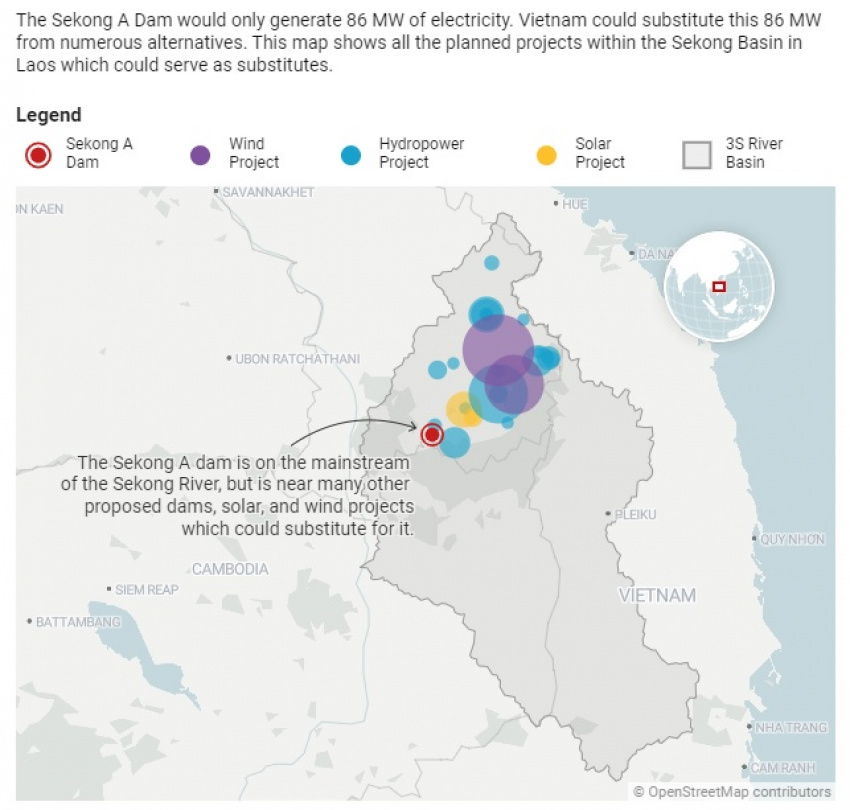

There are numerous alternative power projects that Lao PDR and Viet Nam could develop. The very small amount of power produced by the Sekong A dam could easily be substituted by investing in solar and wind, which would be quicker to build and have zero impact on river connectivity and consequently on sediment delivery and fisheries migration.

If policy-makers prefer to invest in low-risk hydropower, there are many options: about 30 projects with a total capacity of up to 2,000 MW have been identified on tributaries of the Sekong. These dams are located off the mainstream and higher up the river system and would have much lower downstream impacts.

Alternatives to Sekong A Dam:

Photo: Alternatives to Sekong A Dam © the Stimson Center

Photo: Alternatives to Sekong A Dam © the Stimson Center

Solar and wind are booming in Laos. Viet Nam has recently negotiated a power purchase agreement from the first phase of the 600 MW Monsoon wind project in southern Lao PDR. A Thai, Chinese, and Singaporean consortium is considering a 1,000 MW expansion of that wind project for export to the ASEAN market. More than 50 solar projects are undergoing feasibility study in Laos with a total capacity of almost 8,000 MW. Many are floating solar on dam reservoirs, which take advantage of existing transmission lines and benefit from the water’s cooling effect, which increases efficiency. There are four dam reservoirs in Sekong tributaries that could host floating solar, which peaks in the dry season when hydropower declines sharply. For Lao PDR, this would have the added advantage of reducing expensive dry season power imports from Thailand.

So Viet Nam has multiple opportunities to import additional power from Lao PDR in ways that boost government revenue and minimize impacts on sediment and fisheries. A more diverse and less hydropower-dependent power mix would also reduce vulnerability to the more frequent prolonged droughts and saltwater intrusion that become the new normal in the Mekong Delta.

Through Resolutions 120 and 55, Vietnam is transitioning to a more sustainable water and land use in the delta to a much less carbon-intensive energy mix. To achieve these goals, Viet Nam needs to terminate its involvement in the Sekong A dam and replicate its highly successful domestic expansion of solar and wind power in Lao PDR. But as preparatory work on the Sekong A dam continues, Vietnam’s window of opportunity is shrinking. This is therefore a moment of decision for Viet Nam.

This is part two of six web stories produced by the Stimson Center and IUCN under the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation BRIDGE (Building River Dialogue and Governance), a global hydro-diplomacy project that IUCN is facilitating in 15 transboundary river basins, including the Mekong. For the other five webstories, please see:

#1: Vietnam’s COP26 commitments: a moment of truth

#3: Unlocking international finance for Vietnam’s renewable energy transition

#4: Opportunities and challenges in expanding wind in Vietnam’s electricity mix